How Lady Bird Johnson Saw the President Die

Posted by admin on

“Then almost at the edge of town, on our way to the Trade Mart where we were going to have the luncheon, we were rounding a curve, going down a hill, and suddenly there was a sharp loud report—a shot. It seemed to me to come from a building right above my shoulder. Then a moment and then two more shots in rapid succession. There had been such a gala air that I thought it must be firecrackers or some sort of celebration. Then the Secret Service men were suddenly down in the lead car. I heard over the radio system, ‘Let’s get out of here,’ and our Secret Service man who was with us (Rufe Youngblood, I believe it was) vaulted over the front seat on top of Lyndon, threw him to the floor, and said, ‘Get down.’”

–Lady Bird Johnson, White House diary, November 22, 1963

*

Instead, the unimaginable. November 22, 1963, the day in Dallas that, as Bird described it in her first diary entry, “all began so beautifully,” had ended with a flight back to Washington with Lady Bird, the surrogate, now the new First Lady, Lyndon the president, Jack in a coffin, and Jackie a widow. Mrs. Johnson had learned as a journalism student about the use of short sentences to punctuate and give a feeling of drama. Recording her diary eight days after the assassination, she brought that talent to bear in describing one of the most gruesome moments in American history:

We all sat around the plane. The casket was in the hall. I went in the small private room to see Mrs. Kennedy, and though it was a very hard thing to do, she made it as easy as possible. She said things like “Oh, Lady Bird, we’ve liked you two so much….Oh, what if I had not been there. I’m so glad I was there.” I looked at her. Mrs. Kennedy’s dress was stained with blood. One leg was almost entirely covered with it and her right glove was caked, it was caked with blood—her husband’s blood. Somehow that was one of the most poignant sights—exquisitely dressed, and caked in blood.

Bird suggested a change of clothes, but Jackie’s own sense of drama told her to stay in the bloody pink suit in order for “them to see what they have done to Jack.” Bird didn’t stay long with Jackie, but she recorded, before leaving her in the president’s cabin on Air Force One to return to the main cabin, “I tried to express something of how we felt. I said, ‘Oh, Mrs. Kennedy, you know we never even wanted to be Vice President and now, dear God, it’s come to this.’” An understatement.

After Lyndon backed JFK for the vice presidency in 1956, Jack had regifted the prospect of the post to Lyndon in 1960—a gift that had turned out to be far more consequential than they could ever have expected.

There was no chance Lady Bird could fill [Jackie’s] shoes, and that awareness felt oddly liberating.For the Johnsons, the assassination of JFK was another moment in public and private life punctuated and propelled for almost thirty years by death—of politicians whose open seats Lyndon ran for and won; of Lady Bird’s brother and her father in the middle of two of Lyndon’s campaigns; of Lyndon’s mother, the formidable Rebekah Baines Johnson; and of their political father, Sam Rayburn. But with the assassination of John Fitzgerald Kennedy, though the Johnsons gained the presidency, they were left with a profound and pervasive feeling of loss. Kennedy’s death brought Bird a deep “sense of shame over the violence and hatred that has gripped our land.”

The gruesome events of November 22, 1963, had only hardened her desire to repair the breach. “Shame for America! Shame for Texas!” She knew that Dallas was different—more extreme, less tolerant, than the southwest of Austin or the Hill Country of Lyndon’s birth and their home. During the 1960 campaign, she had experienced the virulence of the Dallas coiffed set at a campaign event, where the “Mink Coat Mob” spat at and taunted her and Lyndon, yelling, “LBJ, the Texas traitor!,” “Let’s ground Lady Bird!,” and “LBJ—counterfeit Confederate.” But she also knew that most Americans wouldn’t bother to distinguish one part of the state from another. They just knew that Texas was different, and now Texas was responsible for the assassination of the most wildly popular president since FDR. To add to the insult, a Texan long derided as culturally inferior and suspected as brazenly hungry for power would become commander in chief.

As Bird said, they had “never even wanted” what everyone in Washington regarded as the worst job in American politics, and by inheriting, not winning, the presidency, Lady Bird and Lyndon feared they had lost for good their chance at a legitimate run for the White House.

In Washington and Austin, the Secret Service deployed quickly to gather Luci from Spanish class at the National Cathedral School and Lynda from her dorm at the University of Texas. As of 2:38 p.m. Central Time that Friday, November 22, 1963—less than two hours after JFK was declared dead—their parents were now the president and First Lady of the United States of America.

For the Johnsons, the assassination of JFK was another moment in public and private life punctuated and propelled for almost thirty years by deathWhen Air Force One landed at Andrews Air Force Base, Bobby Kennedy stormed past the Johnsons to find Jackie, and the two in-laws stood as Jack’s coffin was lowered off the plane. After brief remarks, Lyndon and Lady Bird found Jackie and said goodbye to her. They took the short helicopter ride to the White House, where Lyndon repaired to the Old Executive Office Building and Lady Bird and Liz headed by car to the Elms. Together, the two women had helped Jack win Texas, but now their Lone Star State had made him a martyr. “It’s a terrible thing to say,” Liz acknowledged, “but the salvation of Texas is that the governor was hit.” “Don’t think I haven’t thought of that,” the new First Lady replied. “I only wish it could have been me.”

The next day was gray and overcast. Lady Bird left Luci at home with their beagles, Him and Her, to join Lyndon in the Old Executive Office Building, and together they walked across West Executive Avenue to the White House, where President Kennedy’s body lay in state. They met members of the Kennedy clan in the Green Room, the small state parlor generally used for teatime or cocktail hour. From there, the Johnsons followed the Kennedys into the East Room. Bird described the East Room as adorned with a hybrid of American military and Catholic symbols—the chandelier draped in black crepe, “a catafalque in the center and on it the casket, draped with the American flag, and at each corner a large candle and a very rigid military man, representing each one of the [armed] services”—to observe the death of a commander in chief.

Catholic mourning ritual on semipublic display in the White House was surely not what Lady Bird and Lyndon contemplated when they both cautioned their fellow Texans against anti-Catholic bias during the 1960 campaign.

While Jackie dressed in couture, Lady Bird marked a return to a Mamie Eisenhower off-the-rack simplicity.Sunday, November 24, “a bright clear day, of sparkling sun,” was for Lady Bird Johnson “the day I will never forget,” the day President Kennedy’s body lay in state in the rotunda of the Capitol Building. After church services at St. Mark’s on Capitol Hill, the Johnsons joined the Kennedy family again in the Green Room. Eunice Shriver, whom Bird had campaigned alongside three years earlier, told her that Lee Harvey Oswald, Kennedy’s assassin, had been killed. Jackie then arrived, holding the hands of John Jr. and Caroline, both dressed “in two darling blue coats.”

Bird scrutinized every detail, her account of the scene moving, in just a breath, from Oswald’s death to the children’s attire. One detail made her very uncomfortable: White House protocol staff informed the Johnsons that they would ride to the Capitol in the same limousine as Jackie and Bobby. The sharing of confined spaces—this was something the Kennedys and Johnsons had some practice in, most recently two days earlier, during the overheated, too-long wait for LBJ’s swearing in and then their return to Washington aboard Air Force One.

Cognizant of so much pain, Jackie’s and the children’s, and Bobby’s distrust and anger, Lady Bird and Lyndon both would have preferred a separate limousine, to further absorb their fate alone and to give Jack’s widow, brother, and children a measure of privacy.

But they all rode together—Lyndon and Jackie in the backseat, Bobby and Lady Bird on the jump seats, Caroline next to Jackie, and John-John jumping back and forth between his uncle’s lap and his mother’s seat. As the two families left the White House gates, Bird suppressed tears seeing “that sea of faces, stretching away on every side, silent.” Hers would have been a cry, she thought, that channeled the collective trauma on those faces, but the strength and dignity of Jackie and the Kennedy family and “the continuity of strength” the moment required from all of them made it “impossible to permit the catharsis of tears.”

In front of the shared limousine, “Black Jack,” the riderless black horse, boots set in their stirrups but facing backward, symbolizing the fallen warrior, led the procession up Pennsylvania Avenue. Mrs. Johnson’s recording of the day captures the images and sounds and silences of the moment—flags at half-mast, six white horses and the flag-draped caisson, muffled drums. “But most of all was the sea of faces all around us and that curious sense of silence, broken only by an occasional sob.”

Now Texas was responsible for the assassination of the most wildly popular president since FDR.The drive to the Capitol felt interminable. While “the absolutely peripatetic” three-year-old John-John flitted about the limousine, Bobby Kennedy wore “a grave, white, sorrowful face, and there was a flinching of the jaw at that moment that almost made—well, it made your soul flinch for him.” Wearing a black coat on loan from Nancy Dickerson, Lady Bird, along with Lyndon, followed the Kennedys as they entered the rotunda, where an honor guard stood around JFK’s flag-draped coffin. Bird watched as Lyndon laid a wreath at the foot of the casket.

When the funeral procession was over, Bird, relieved to be at least departing the Capitol in a separate limousine from the Kennedys, fixed her attention, like the rest of the country, on Jackie, but also cast an indirect spotlight on how the very difference between the two women would help Mrs. Johnson craft her own public identity.

To me, one of the saddest things in the whole tragedy was that Mrs. Kennedy achieved, on this desperate day, something that she had never quite achieved in the years she’d been in the White House—that is—a state of love, a state of rapport between her and the people of this country. I mean the sort of people who write their Congressman on tablet paper with a pencil. Her behavior from the moment of the shot until I said goodbye to her the other day is, to me, one of the most memorable things of all. Maybe it’s a combination of great breeding, great discipline, [and] great character. I only know it’s great.

Meditating on their relationship, Lady Bird felt “something of a gulf ” open up between herself and the Kennedys. But her instinct was to bridge it.

With her own eye for public theater and mythmaking, Bird was onto something, and she instinctively appreciated how, in the aftermath of the president’s death, achieving greatness for John Fitzgerald Kennedy emerged as Jackie’s overriding aspiration and ultimately became her most significant accomplishment.

In planning every detail of public mourning—echoing President Lincoln’s funeral, personally vetting the invitation list, hand-designing the invitations to the Mass at the Cathedral of St. Matthew, choosing a burial site at Arlington National Cemetery over a local plot in Boston, the way she sited and adorned his grave, and her inclusion of her children in the most public of rituals—Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy solidified the exquisite balance between democracy and monarchy that she and Jack had cultivated so expertly during their one thousand days in office. With all this, she ensured the enduring image of the Kennedy White House as the modern era’s “there-will-never-be-another” Camelot.

“Everything she has done,” wrote Mary McGrory, “seems to be a conscious effort to give to his death the grandeur that the savagery in Dallas was calculated to rob it of.” Bringing “meaning to tragic chaos,” Jacqueline Kennedy “has borne herself with the valor of a queen in a Greek tragedy.” There was no chance Lady Bird could fill such shoes, and that awareness felt oddly liberating.

Lady Bird and Lyndon feared they had lost for good their chance at a legitimate run for the White House.Still, comparisons between two such different presidential couples were inevitable and irresistible. One couple was glamorous, the other pedestrian; one was cultured, the other not so much. One throbbed with youth, and the other was sedate in middle age. The Harvard Brahmin life and education that bespoke intellectual sophistication was set off against the bare-knuckle hillbilly instincts from Texas.

To the world, Kennedy’s deployment of power was optimistic and enlightened, as opposed to the perception of Johnson’s cynical and likely racist backroom manipulations, LBJ’s leadership of the 1957 civil rights bill notwithstanding. While Jackie dressed in couture, Lady Bird marked a return to a Mamie Eisenhower off-the-rack simplicity. All these truisms do what they always do: simplify and obscure, but also suggest some core truth.

Abbreviated as it was, Jack and Jackie Kennedy’s presidency, in dramatic contrast to the square Republican stoicism of Ike and Mamie’s sexless White House, was indeed completely different from what the Johnsons would and could deliver. In temperament and public persona, Jack and Jackie were radically different from Lyndon and Lady Bird. For all that Lady Bird and Jackie may have shared as the wives of presidents, Jackie despised politics. “She breathes all the political gases that flow around us but she never seems to inhale them,” Jack said in 1959.

Politics for Lady Bird, in contrast, had, by 1948, Lyndon’s first Senate campaign, become her daily infusion of oxygen, her second skin. And yet Jackie—the reluctant public figure, the First Lady determined to ensure her children’s privacy, who avoided most of the traditional ceremonial duties of the position, who frequently fled Pennsylvania Avenue to yacht and to hunt and to escape the humiliations of Jack’s profligate liaisons—still managed to make herself an asset to the president on the global stage and to make her own mark on the White House and on the country at large.

___________________________________

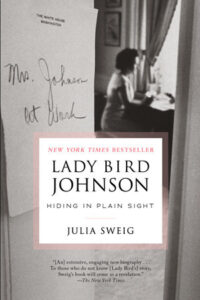

Excerpted from Lady Bird Johnson: Hiding in Plain Sight by Julia Sweig. Copyright © 2021. Available from Random House, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.