Every Thought I Had While Watching 2001: A Space Odyssey

Posted by admin on

As the outer-space correspondent at The Atlantic, I spend a lot of time looking beyond Earth’s atmosphere. I’ve watched footage of a helicopter flying on Mars. I’ve watched a livestream of NASA smashing a spacecraft into an asteroid on purpose. I’ve seen people blast off on rockets with my own eyes. But I have never seen 2001: A Space Odyssey.

This is an enormous oversight, apparently. The 1968 film is considered one of the greatest in history and its director, Stanley Kubrick, a cinematic genius. And, obviously, it’s about space. Surely a space reporter should see it—and surely a reporter should take notes.

What follows is my real-time reaction to watching 2001 on a recent evening, edited for length and clarity. Even though the movie has been out for 54 years, I feel a duty to warn you that there are major spoilers ahead. (If you’re suddenly compelled to watch 2001 first, you can rent it for $3.99 on YouTube.)

The movie kicks off with orchestral music that you’ve probably heard whether or not you’ve seen 2001, a heart-thumping and foreboding melody, with that dramatic bum … bum … BA-BUM. (It’s “Also Sprach Zarathustra,” by the German composer Richard Strauss.) The sun rises over a flat, grassy plain. We slink from shot to shot of the landscape. Some people had warned me that 2001 is pretty slow-moving, but it is slooow-moooving. We’re a few minutes in when my partner, sitting next to me on the couch, asks if we can watch this at 2x speed.

Here come some primates. Well, a bunch of actors dressed up in furry costumes and prosthetics. Another group of apes arrives, apparently eager to take over our protagonists’ watering hole. There’s a lot of hooting and bouncing around until the rival troop leaves. Later, the animals huddle together in a cave to sleep. As we move through these vignettes of ape life, I’m half-expecting David Attenborough to chime in.

[Read: Why the Mars movie is the space-age Western]

It’s morning again on what feels like the 17th day on the prairie, and a tall, black monolith is sticking out of the ground. Looks kind of like a giant remote control without the buttons. So much jumping, so much crouching; are these actors’ knees okay? Later, one of the apes plays lazily with an animal bone, but then something clicks and he starts furiously bashing the skeleton in front of him. “Also Sprach Zarathustra” starts up again. Ah, yes, these are hominids, early humans, and this must be a milestone in their evolution, brought on by the arrival of the otherworldly monolith. (I’m reminded of those silver monoliths that mysteriously showed up in Utah and a few other places in 2020, but those were definitely not otherworldly.) After a fight with the rival troop, an ape hurls the bone into the sky and, in a smooth split-second transition, the object becomes a satellite floating in space. We’re in the future now! Maybe there will be some dialogue?

Spaceships are everywhere around Earth. The planet looks wrong to my modern eye, like a watercolor illustration, with oceans more turquoise than the azure I’m used to. It’s the worst-looking thing in the movie so far, probably because 2001 came out before people really knew what Earth looked like from space—before Apollo 8’s “Earthrise” photo, taken from lunar orbit in late 1968, and before Apollo 17’s “Blue Marble” shot from 1972, which captured the whole world for the first time.

Still, the special effects in 2001 are fantastic. Inside one of the spaceships, a loose pen floats in microgravity, its movements seamless. How did they do that without CGI? The spacious interior looks like a luxury airliner, and a man with neatly coiffed hair dozes in his seat and—wait, are you telling me he’s the only passenger on this space-plane? How wasteful. A flight attendant wears special grip socks that keep her steady as she walks upright down the aisle. Clever.

The ship arrives at its destination, the Hilton Space Station 5. Heywood Floyd, now awake, clears customs with a futuristic voice-confirmation system, then videochats his young daughter to say that he’s going to miss her birthday because of work. Floyd meets with some Russian scientists who tell him that there’s something fishy going on at an outpost on the moon. The Russian accents are very bad, but I suppose it would have been frowned upon to cast Russian actors in a Hollywood film at the height of the space race.

[Read: How ‘The Fifth Element’ subverted sci-fi movies]

Floyd takes another flight where he is the sole passenger, this time headed to the moon. The spaceship bathroom has a sign with a 10-step guide to using a zero-gravity toilet. This is remarkably prescient on Kubrick’s part: Astronauts get asked how they go to the bathroom in space all the time. I look across the couch and see that my partner has fallen asleep.

Floyd takes a meeting on the moon and congratulates the staff there on their tremendous discovery: a black monolith (gasp!) that appears to have been buried in the lunar surface 4 million years ago. Floyd and the others suit up in some spiffy, formfitting space suits and head out to the site. 2001 premiered a year before Apollo 11 landed on the moon, but Kubrick somehow nailed the look of the lunar surface. This is more impressive than any plot element yet! The men pose for a picture with the monolith—cute—but then there’s a high-pitched beeping noise and they’re bowled over. Kubrick offers no hint of what that all means, which I’m starting to realize might be his whole thing.

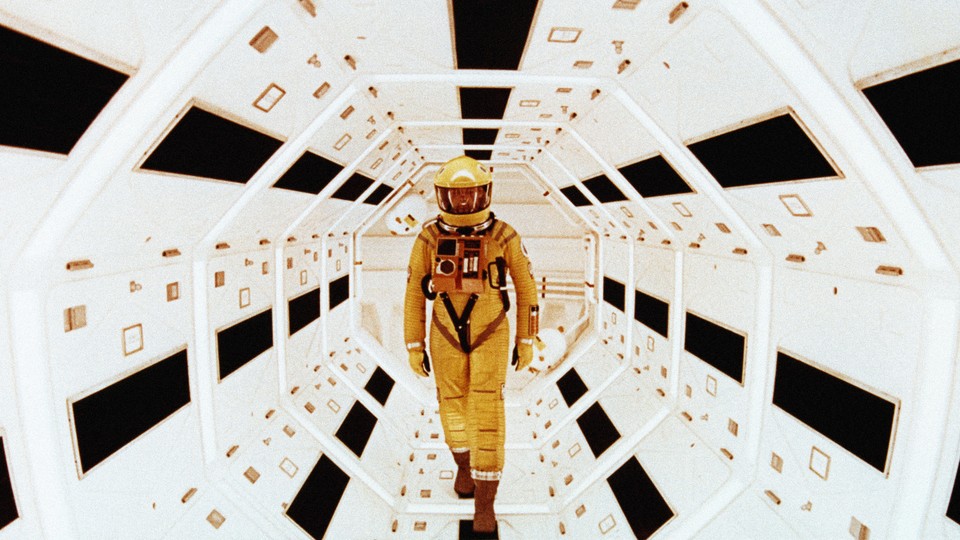

Fast-forward 18 months and a crew of five men are on their way to Jupiter. This is a great-looking spaceship, especially the living quarters, which are constantly spinning to produce their own gravity. Once again, well done, SFX team. I wish I could have experienced this without a 21st-century brain spoiled by Gravity. Three of the five astronauts are cryogenically frozen for the ride, while the remaining two are assisted by a supercomputer called HAL 9000. “No 9000 computer has ever made a mistake or distorted information,” HAL says in a soft monotone. I’m cracking up. This is the most glaring foreshadowing I’ve ever seen. “I love people,” the computer says. “They are my friends.” The AI is definitely going to play nice and not do anything to sabotage this mission.

HAL reports a glitch with a device on the exterior of the spaceship, and one of the awake astronauts, Dave Bowman, takes a little pod outside to check it out. Bowman floats out of the pod—completely untethered?!—and grabs on to the side of the ship, takes out the device, and goes back inside. All of this unfolds extremely slowly. My partner has woken up, but now I’m falling asleep.

[Read: The absurdity of the ‘First Man’ flag controversy]

The action is picking up, though, ever so slightly. The astronauts examine the device and find that there’s nothing wrong with it. Mission control back on Earth tells them that HAL was wrong, but the computer insists that the cause is human error, and suggests that Bowman and his colleague, Frank Poole, go back out there. The astronauts, now suspicious of HAL’s motives, sneak into a pod and cut off the vehicle’s communication lines so the computer can’t overhear them. YOU FOOLS. You’re still facing the dang computer, and HAL can read your lips! When Poole heads back out, HAL commands his pod to kill the astronaut. As Bowman sets out in his own pod on a (too-late) rescue mission, HAL shuts down the systems for the cryocoffins, killing the astronauts inside. Bowman asks HAL to open the pod-bay doors so that he can come back in with Poole’s body. HAL refuses, delivering the film’s most famous line: “I’m sorry, Dave. I’m afraid I can’t do that.” The computer taunts Bowman: How are you going to get back in without your helmet, buddy?

Okay, pause. PAUSE. Bowman, presumably a professional astronaut, did not take his space helmet with him before exiting the space station. There it is, still in the pod room, hanging like a forgotten winter hat on a coat rack. I am howling. Listen, I’m not the kind of space reporter who nitpicks the physics of sci-fi movies and complains about them being unrealistic. My favorite space movie is Interstellar, in which Anne Hathaway seriously suggests that love can transcend space and time. But this—Dave Bowman forgetting his helmet—I cannot accept. It is the most unbelievable part of 2001.

Bowman, desperate and helmetless, uses a propulsive mechanism in the pod to blast himself into space and toward the air lock, which he somehow manages to open manually without asphyxiating. Then, wearing a helmet this time, he heads to the control room to shut down HAL. Man has triumphed over machine. A screen comes alive with a prerecorded video that reveals that humans mounted this mission after the monolith on the moon, the first evidence of intelligent alien life, aimed a radio transmission at Jupiter.

The ship reaches Jupiter and, would you look at that, there’s another black monolith just floating around near the planet. Bowman goes out in a pod to investigate it but ends up sucked into some kind of wormhole. What follows is a spectacular sequence of colorful lights that makes clear why 2001 became such a hit with stoners. The psychedelic display is interspersed with quick shots of Bowman, who has kept his cool throughout the film, freaking out. Wormholes are a classic sci-fi trope, and I wonder where this one, which surely inspired all the rest, will spit Bowman out. The answer: an elegantly designed bedroom. What?!?

[Read: The dimming of Stanley Kubrick]

An astronaut appears. It’s Bowman, but slightly older, with wrinkles at his eyes. My dude is freaking out again, and aging rapidly. (I didn’t think anything in this movie could happen rapidly.) He’s looking at his reflection in the mirror when there’s a clattering noise behind him—someone is sitting at a table in the middle of the room, eating. It’s an even older Bowman, and slightly older Bowman is gone! Even-older Bowman, now in a robe instead of a space suit, bumps a crystal glass of wine and it falls to the floor, shattering. He looks across the room—and is replaced by a still-older Bowman, hairless and crinkly, in bed. Still-older Bowman raises his arm and points to something standing at the foot of the bed: a monolith. The giant remote control says nothing. Cut back to the bed and still-older Bowman is now a … glowing baby orb? The infant, encased in a blue bubble, floats through space toward Earth, its eyes wide. And that’s it.

That’s it?!? I am completely befuddled and unsatisfied. I was expecting 2001 to be a movie, consisting of those elements that make movies great: plot, character development, and, you know, a decent amount of dialogue. 2001 is two hours and 23 minutes long, slightly shorter than the usual modern-day superhero movie; for comparison, the run time of 2018’s Avengers: Infinity War is two hours and 29 minutes. But 2001 has just 40 minutes of speaking, whereas the superheroes are a chatty bunch. And what am I supposed to do with that ending?

A few days after 2001 opened, Kubrick told an interviewer that “the power of the ending is based on the subconscious emotional reaction of the audience, which has a delayed effect.” So I decided to sleep on it. The next morning: nothing. I understand that the mysterious appearance of the monoliths seem to kick-start a new step in humankind’s evolution, and that the star baby was probably on its way to impart some time-warping knowledge to the unsuspecting inhabitants of Earth. I acknowledge that my impatience with the slow pacing could stem from the fact that movies move much quicker now than they did in the 1960s (though some reviewers did describe it as dull back then). But really, the film seems rather overhyped.

Should I just say I loved 2001: A Space Odyssey? I’m sorry, everyone. I’m afraid I can’t do that. 2001, I know now, is not so much a movie as it is an artistic exercise, a vibe. It is, as one of my colleagues put it the day after my viewing session, two hours of Kubrick shouting at the viewer that he is an artiste. I’m with Renata Adler, a former New York Times critic, who reviewed the film as “somewhere between hypnotic and immensely boring.” Yes, 2001 is a visual marvel. But I don’t think I liked it.